Fire is a chief metaphor for the Internet: it is metaorganic; it extends the range of (informational) food; it empowers people to explore new time zones (the night) and territories of knowledge; it increases some kinds of sociability, demands ongoing maintenance, and produces dangers and externalities that did not exist before. Fire was the first World Wide Web, a fragile system for contagious spreads.

(The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media)

Thus it was only fitting that at DWeb Camp 2023, we gather around a literal campfire to talk about this metaphorical fire that has seeped into so much of our lives.

DWeb originates as a technical term, short for the ‘decentralized web’. It refers to new web technologies and communities seeking to reduce or eliminate central points of control on the web.

The internet’s original creators intended decentralization to be a core value, aiming to make information accessible to all and connect people worldwide. They believed, rightfully so, that the web is a genuine social accomplishment and that we should look after it by improving and preserving it. They believed that the ability to ‘modify source’ — the ability to make and remake software to better serve them — was critical to a thriving, diverse, and resilient web.

Yet, looking at the web today we see very little of these patterns. It’s no longer a controversial statement to say that, as citizens of the internet, we have lost our ability to shape the web and make it a home.

However, just blindly decentralizing the web won’t fix it. DWeb also asks the questions of what we are decentralizing and for whom1?

Computer scientists and academics see decentralize the web as a call for architectural and maybe logical decentralization: we should decentralize the actual physical hardware of the system and ensure that there is no central point of failure. If you cut the system in half, will both halves continue to fully operate as independent units?

Technology critics, philosophers, and activists see decentralize the web as a call to interrogate the power structures behind this infrastructure. How many individuals or organizations ultimately control the computers that the system is made up of? After all, what’s the point of decentralizing all the hardware if 5% of all the users own 95% of it anyways?

These approaches are not mutually exclusive and in fact should be considered in unison. To me, DWeb as a term has evolved beyond just the actual technical term ‘decentralized web’ and is now a banner for people who also believe that these two questions are both asking and in conjunction.

DWeb Camp exists because the founders believed that we couldn’t just have the technologists and entrepreneurs building away in one realm and the academics, philosophers, and critics theory-making in another. Rather, they wanted to create a space where both of these types of people could co-exist, learn from each other, and leave eventually having become a bit of the other — the technologist a little more critical, and the critic a little more pragmatic.

To me, this is what makes DWeb so special. So rarely do you find a space where you can find people who are on-the-ground activists during the day and avid protocol researchers by night. People who care about both the “what” and the “why”2. These are people that don’t just preach the gospel of ‘decentralization good’, but themselves live in contexts where these values actually make a tangible difference in their lives.

And, perhaps most importantly, they know how to do it all while being kind, empathetic, and quirky in the way that you know they’ve spent too long growing up on internet to not care about the future of it.

This year at DWeb Camp, Spencer Chang and I hosted a session asking campers to gather their collective imaginations and dreams for what a communally-owned internet could look like.

We have a lot of dystopian fiction and a lot of reminiscing, but not a lot of forward-looking dreams for the web. Dreaming is an important piece of fiction that rallies people to articulate a vision they want to make a reality. In hosting this session, we recall Ruha Benjamin: “to see things as they really are, you must imagine them for what they might be”.

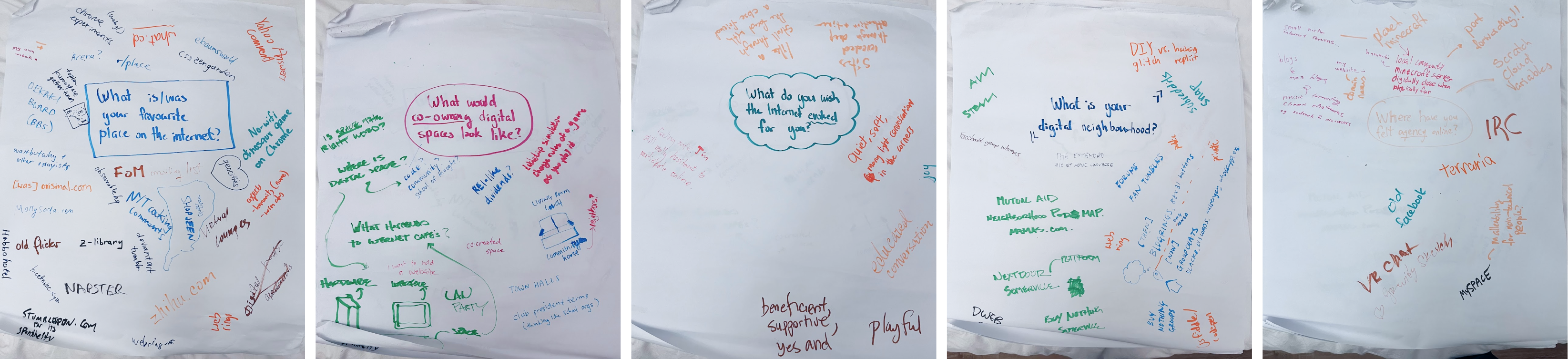

Our session focused around circulating 5 sheets of paper, each with a question on it:

- What do you wish the Internet evoked for you?

- What would co-owning digital spaces look like?

- What is your digital neighbourhood?

- Where have you felt agency online?

- What is/was your favourite place on the internet?

We started by reminising: remembering sacred spaces like Club Penguin, obscure math mailing lists, torrent communities, and hobby forums. We discussed the feeling that existing on the internet feels like living on rented ground. We recalled architects and urban designers like Christopher Alexander who first noticed that rental areas are always the first to turn to slums and the importance of owning your own home3, drawing parallels to our digital spaces.

We wondered how to make it possible for the average layperson to be able to change and adapt software for their own needs; for them to experience creating software not like a professional chef, but a home cook. One group noticed how users consistently still subvert these platforms and create folk usages of software, paving our their own desire paths. We forayed into the realms of convivial software and the movement to make building software fun again and wondered how to give people the ability to be architects of their own digital homes again.

To us, the session was a reading of ‘decentralized’ not in the pure technical or power sense of the word. Rather, we read ‘decentralized’ to mean communally governed and owned infrastructure.

We wondered about what digital infrastructure coops could look like; hosting little websites and apps for just our communities rather than at global scale. We thought about how community-owned infrastructure could mean that digital autonomy enables more physical and bodily autonomy rather than take away from it. Many participants mentioned how their own projects and organizations used decentralizated infrastructure and governance to help their local communities to better provide financial support for gender-affirming care or speak-out about tyrannical governments more safely, consistently, and reliably.

We wondered how data can be used as something to share as a gift between friends rather than extracted without consent. We also thought about how cool and whimsical it would be if we could have tiny little windows into the digital homes of our friends, and be hosted just like we would be able to be in the real world.

Reclaiming our agency and ability to communally construct our digital spaces starts from people willing to dream and fight for it.

In many ways, this session (and the greater DWeb Camp as a whole) felt like gathering of people who haven’t given up on the inherent good of the internet and are fighting for this future where anyone can be an architect of their own digital experience. It’s a pretty special place.

Footnotes

-

Val Elefante, another fellow, wrote about this in-depth in their piece on Coalition-building Across the Tech Stack. If you are interested in a more critical analysis of decentralization, go read their piece! ↩

-

These terms come from a wonderful session hosted by Fight for the Future on technology that supports various abortion and gender affirming care funds and their beneficiaries. See also: Design Justice ↩

-

“Rental areas are always the first to turn to slums. The mechanism is clear and well known. See, for example, George Sternlieb, The Tenement Landlord (Rutgers University Press, 1966). The landlord tries to keep his maintenance and repair costs as low as possible; the residents have no incentive to maintain and repair the homes – in fact, the opposite – since improvements add to the wealth of the landlord, and even justify higher rent. And so the typical piece of rental property degenerates over the years. The landlords try to build new rental properties which are immune to neglect – gardens are replaced with concrete, carpets are replaced with lineoleum, and wooden surfaces by formica: it is an attempt to make the new units maintenance-free, and to stop the slums by force; but they turn out cold and sterile and again turn into slums because nobody loves them.” (p.394, Your own home, A Pattern Language) ↩