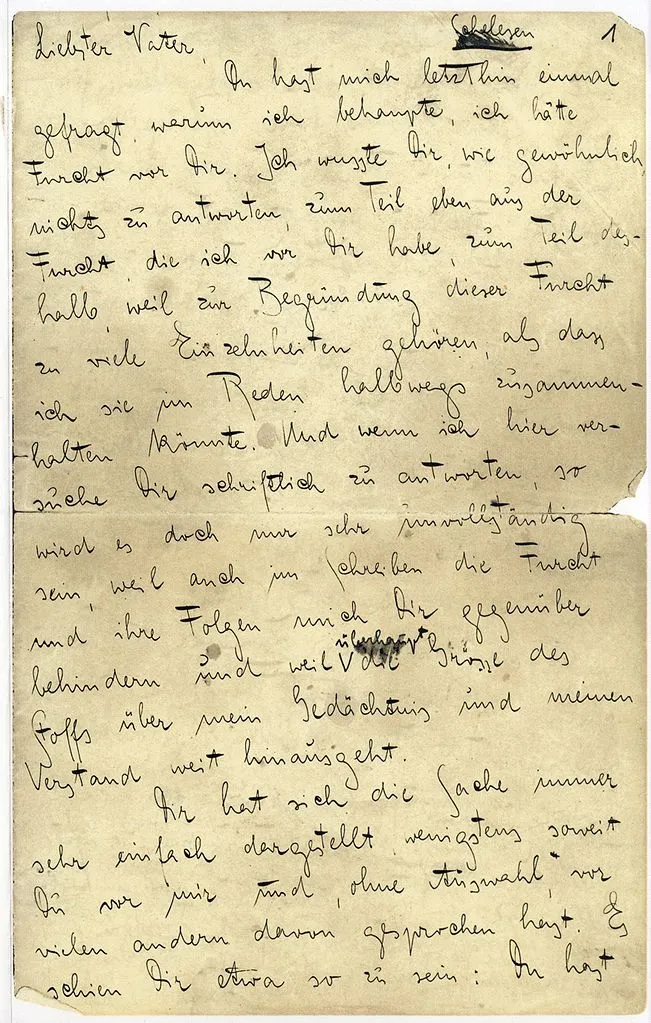

Letter to his father

Excerpts from Maria Popova in The Marginalian

The anguish resulting from a disparity of temperaments coupled with a disparity of power between parent and child is familiar to all who have lived through a similar childhood — the constantly enforced, with varying degrees of force, sense that the parent’s version of reality is always right simply by virtue of authority and the child’s always wrong by virtue of submission, and thus the child comes to internalize the chronic guilt of wrongness.

A heartbreaking effect of these disorienting double standards is that we as children grows utterly confused about right and wrong, for they seem to trade places constantly depending on who the doer is, and comes to internalize the notion that he or she is always at fault.

The most devastating pathology of such relationships is the child’s compulsive effort — be it by vain hope or by concrete action — to eradicate the abusive parent’s demons and make the paltry angels endure, only to be disappointed over and over again every time the demons re-rear their undying heads.

Quotes

“you do charge me with coldness, estrangement, and ingratitude. And, what is more, you charge me with it in such a way as to make it seem my fault, as though I might have been able, with something like a touch on the steering wheel, to make everything quite different, while you aren’t in the slightest to blame, unless it be for having been too good to me.”

“You can only treat a child in the way you yourself are constituted, with vigor, noise, and hot temper, and in this case this seemed to you, into the bargain, extremely suitable, because you wanted to bring me up to be a strong brave boy.”

“I was continually in disgrace; either I obeyed your orders, and that was a disgrace, for they applied, after all, only to me; or I was defiant, and that was a disgrace too, for how could I presume to defy you; or I could not obey because I did not, for instance, have your strength, your appetite, your skill, although you expected it of me as a matter of course; this was the greatest disgrace of all.”

“Now you are, after all, at bottom a kindly and softhearted person (what follows will not be in contradiction to this, I am speaking only of the impression you made on the child), but not every child has the endurance and fearlessness to go on searching until it comes to the kindliness that lies beneath the surface. You can only treat a child in the way you yourself are constituted, with vigor, noise, and hot temper, and in this case this seemed to you, into the bargain, extremely suitable, because you wanted to bring me up to be a strong brave boy.”

“Hence the world was for me divided into three parts: one in which I, the slave, lived under laws that had been invented only for me and which I could, I did not know why, never completely comply with; then a second world, which was infinitely remote from mine, in which you lived, concerned with government, with the issuing of orders and with the annoyance about their not being obeyed; and finally a third world where everybody else lived happily and free from orders and from having to obey”

“It is also true that you hardly ever really gave me a whipping. But the shouting, the way your face got red, the hasty undoing of the braces and laying them ready over the back of the chair, all that was almost worse for me. It is as if someone is going to be hanged. If he really is hanged, then he is dead and it is all over. But if he has to go through all the preliminaries to being hanged and he learns of his reprieve only when the noose is dangling before his face, he may suffer from it all his life. Besides, from the many occasions on which I had, according to your clearly expressed opinion, deserved a whipping but was let off at the last moment by your grace, I again accumulated only a huge sense of guilt. On every side I was to blame, I was in your debt.”